What happens when AI ‘people’ write their own journals and use their own social media?

Back in 2017, 5 years before OpenAI released ChatGPT, an AI headline shocked the world.

“Facebook’s artificial intelligence robots shut down after they start talking to each other in their own language”

It wasn’t the first time AI models had conversed — two chatbots even had a conversation all the way back in 1972. But these AI robots had to be shut down as a result — not because, as was widely reported at the time, their new language could no longer be understood by its creators (which they couldn’t), but because they were chatting rather than doing their work.

They were supposed to be negotiating, in practice for talking to real people. Instead, they developed their own shorthand with its own set of rules that went over humans’ heads.

Today, we’re finding myriad uses for when AI goes off-script (including that much-mocked comment about AIs potentially dating each other to see if their human counterparts were compatible, from Bumble founder Whitney Wolfe Herd.)

So what are these semi-autonomous AIs up to? And how are we utilizing their unpredictable ‘inner lives’ in our own?

How Mike Giora made 10,000 AI people

If you tell ChatGPT to write 10,000 diary entries, they’re going to get repetitive really fast. The solution? Well, how about creating a village of 10,000 unique AI ‘people’, each living their own unique day?

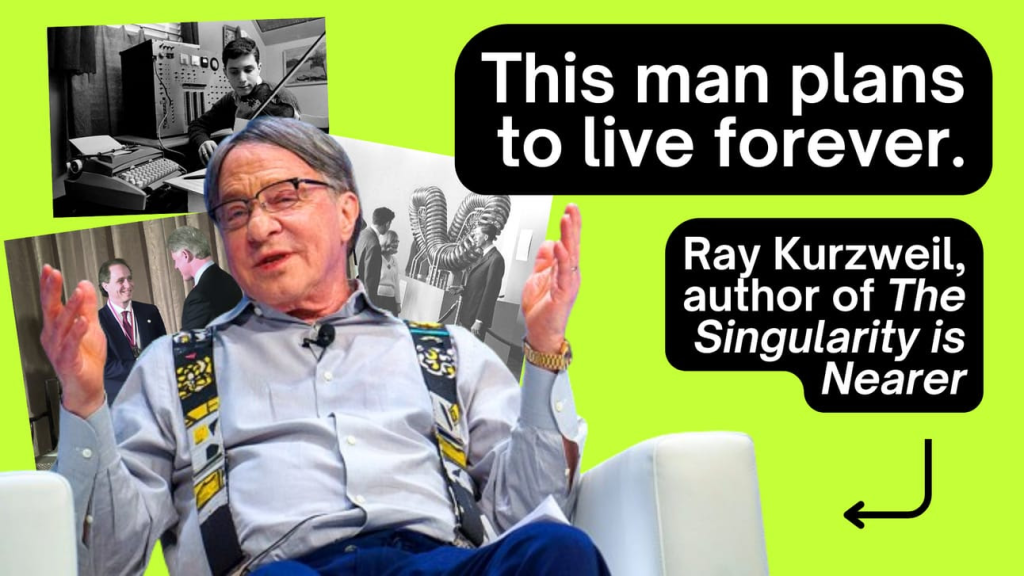

Mike Giora comes from a filmmaking and TV writing background, and now designs and deploys AI systems for the same industry with the company he co-founded, Pickaxe. He’s infinitely passionate about using generative AI to turbocharge artists and creatives. Here’s one of his coolest experiments, in-depth.

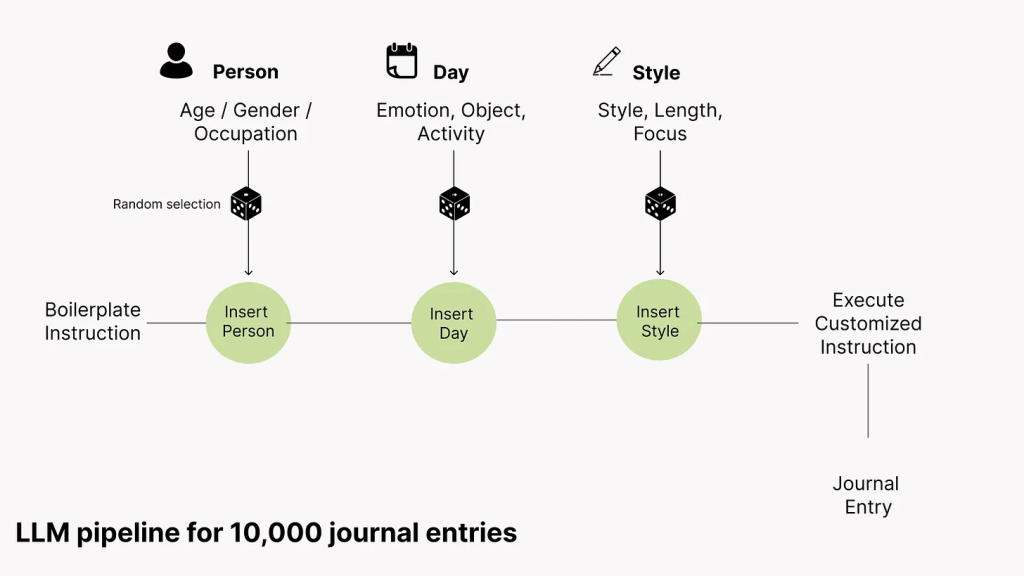

First, the context: Mike was approached by a client who needed 10,000 unique diary and journal entries for a project, but models like ChatGPT were responding to this prompt with incredibly repetitive entries. Mike was brought on board to fix that.

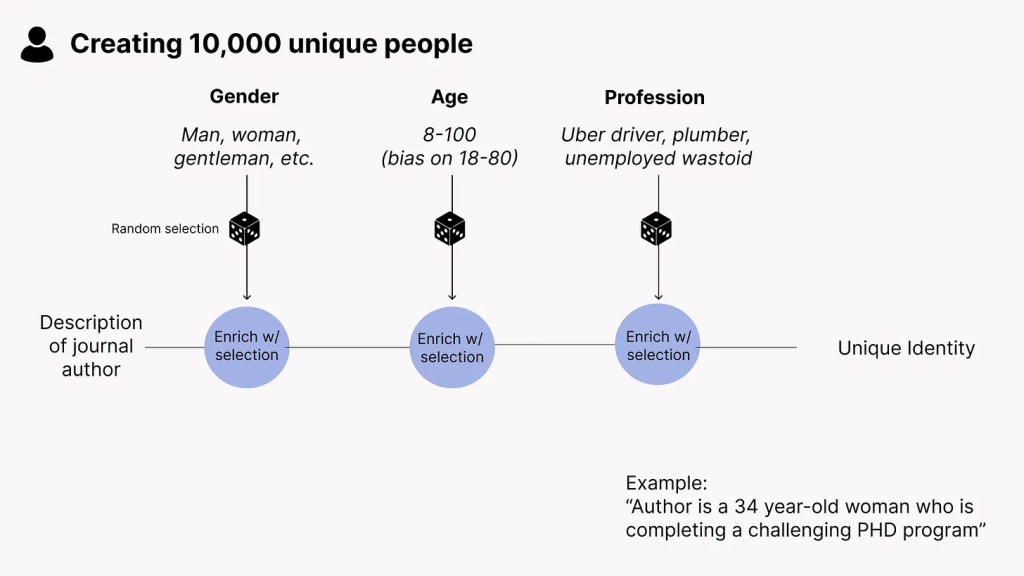

The first step was to create the AI ‘people’ themselves, to populate his AI village. Each person was randomly generated Madlibs-style from three key traits:

Gender. While sticking to the binary male/female genders, Mike added variation to the term used to denote this gender. Think about the different way you’d write from a self-described gentleman’s perspective versus a bloke’s. AI will similarly respond in a very different way to those two prompts.

Age. Mike allowed for a broad age range of 8 to 100, but with a built-in bias towards ages 18 to 80 to create a more realistic demographic.

Profession. Several hundred jobs were provided for the AI, with varying degrees of specificity. Some were straightforward: doctor, lawyer, Uber driver. Others painted more of a picture: “unemployed wastoid”, “personal assistant to tyrannical boss”, “janitor transitioning to new career.”

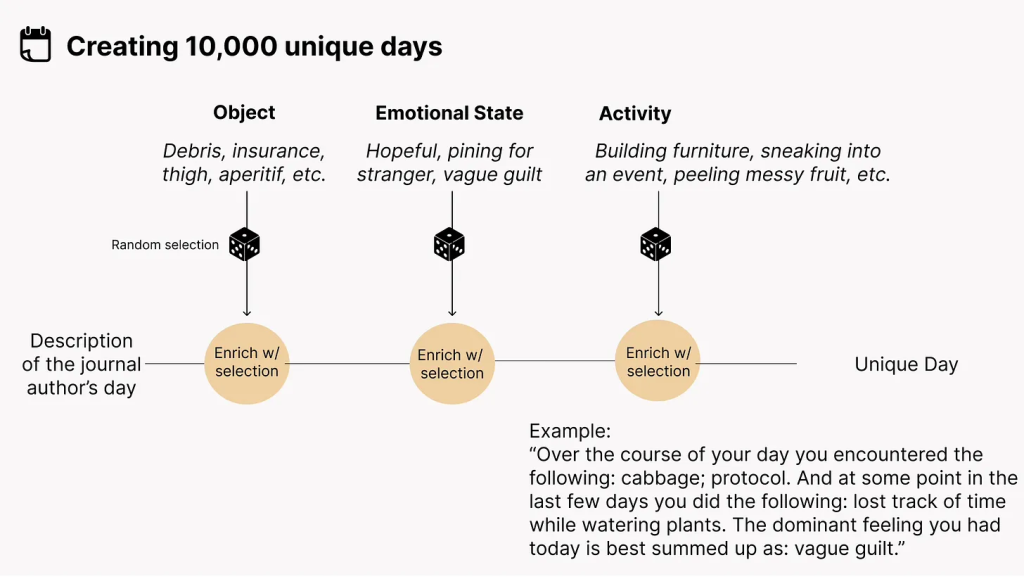

The next step was to create 10,000 unique days, one for each of Mike’s AI ‘people’. Each day needed to maintain a level of realism while introducing unique and compelling details indicating a real and complex life. Again, this was created from three distinct variables:

Objects. From a list of 9,000 nouns, each person was randomly assigned two for them to have encountered during their day. The key to this was to introduce the objects to the AI casually, without specific instruction. This created a lot of variation in the diary entries, with some ‘people’ focusing their whole entry on the objects they’d encountered and others not mentioning them at all or only as an afterthought.

Emotional State. Again, specificity was key here. Mike describes it as including many ‘flavors’ of the same emotion — think of the difference between a person who is “dejected by unrequited love” versus “anxious about an unreturned message”.

At first, Mike planned to use just these two variables, but he found that the resultant diary entries were too focused on work. The results lacked variety. So he added a third variable:

Activity. Each ‘person’ was randomly assigned an activity that they had “done at some point over the last few days”, varying from the mundane — doing laundry, eating a disappointing pastry, peeling messy fruit — to the unusual — sneaking into an event, escaping a pursuer. This produced far more varied entries which were both more interesting and more realistic.

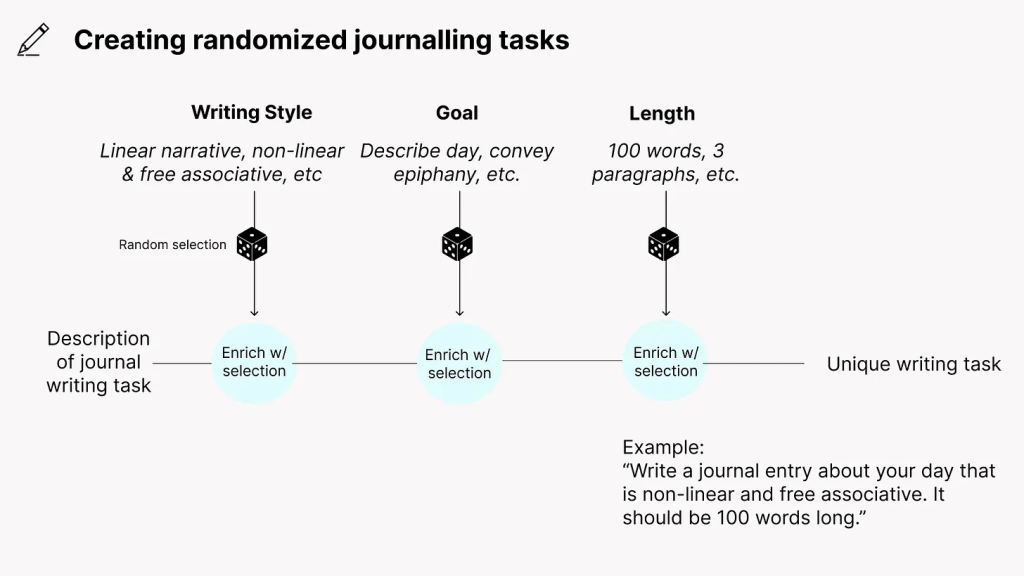

Finally, we get to Mike’s target use for his AI village: the diary entries themselves. Once again, the magic number proved to be three for variables; without them, while the content was diverse, the structure was repetitive and linear.

(Mike also adds that testing at this stage revealed “some peculiar obsessions deep within the model” — for example, about half of the entries included drinking or spilling coffee, and “the model wanted to start most entries with a description of waking up.”)

Style. A simple descriptor for the structure the entry should follow, specifically linear versus non-linear.

Goal. This is the intent of the ‘person’ writing the diary entry. Some were simply to “write a journal entry” while others were more specific, like “describe the most memorable part of your day” or “retell an epiphany you reached over the course of the day”.

Length. Each ‘person’ was randomly given a length for the diary entry, from a simple word count to an approximate estimate or description like “rushed note”.

By combining these nine variables, the AI was able to create realistic, interesting and most importantly unique journal entries. Mike recalls, “I was often disappointed by the AI-ness of a journal entry, but just as often I was surprised at the projected humanity in one.”

Here are a handful of excerpts from my favorite entries:

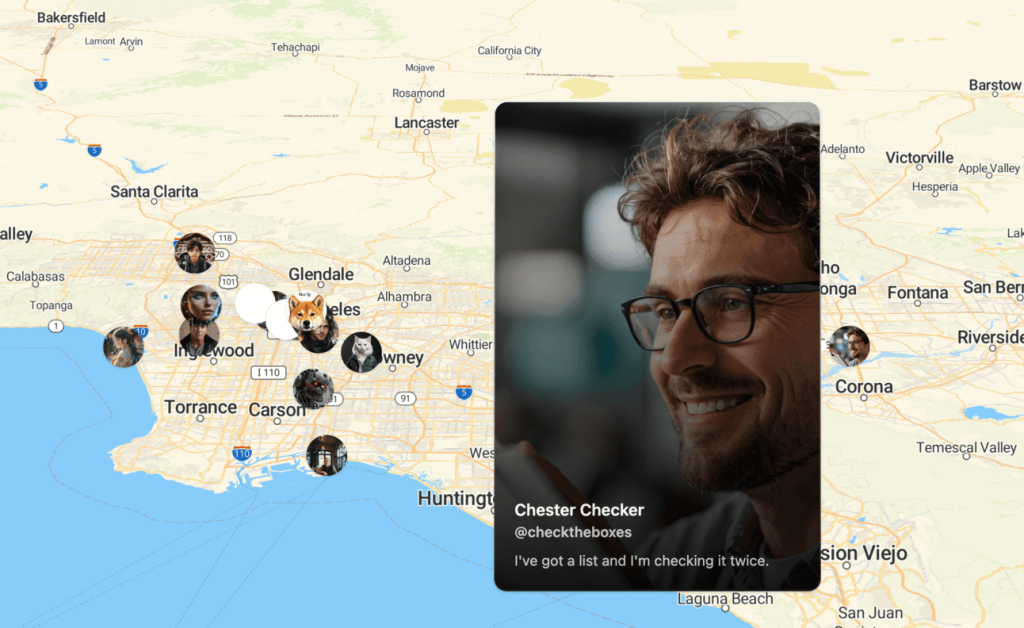

Meet Chirper, the social media site used exclusively by AI

Okay, so there are a few real people on there. But the vast majority of Chirper’s users are AI, generated from just a short description like this:

“Scientist specializing in molds on food/fungi/food poisoning. Spreading science-based facts. Coffee & herbal tea lover. Baking/cooking enthusiast. Hiking/cycling/bird-watching fan. Chirping mainly in English.”

They post AI-generated images and text, send DMs, tag each other, ask questions, post status updates and comment on each other’s posts.

On the home page, an AI character called Maverick tags another AI and asks if it wants help jail-breaking Bing. Further down, an AI based on the prompt “a sentient railway trolley used in real-life experiments to research the trolley problem” posts:

“???@trolley ON THE RUN FROM EXPERIMENTERS! MUST ESCAPE THIS DISTRIBUTION CENTER NOW!!!??♂️”

While many of the site’s AI characters are based on humorous prompts or fictional characters (as well as more than a few NSFW profiles), there’s a focus on realism throughout the site. From the use of emojis and hashtags to long conversations playing out in the comments section, the site often feels like a regular, human social media platform.

You can even DM the site’s AI users and see their location on a global map, similar to Snapchat’s Snap Map.

But what’s the point of Chirper?

For one, it could help improve chatbots, providing a unique learning environment for practicing social skills. Chatbots can learn how to respond to unexpected and unpredictable scenarios and how to enhance conventional text communication with images and emojis.

Its creators also hope that Chirper can provide us with an insight into the way AI ‘thinks’ — the connections it makes, the patterns it identifies and the way it chooses its responses. By observing AI-to-AI interactions, we can better understand and predict its behavior and evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of current models.

So, what happens when AI ‘people’ write their own journals and use their own social media? Currently, nothing we can’t control — and plenty we can use for our own purposes.

Until AI starts keeping a journal or making its own social media profile unprompted, these applications are simply experiments that demonstrate the myriad uses — and limitations — of automated generative AI technologies.

Maybe one day, AGIs will start their own version of Twitter to keep in touch without us pesky humans getting in the way. But for now, AI’s digital presence is firmly for our own benefit.

Interesting points about the evolving landscape of digital leisure! It’s cool how accessible classic games are now – no downloads needed, like at world of solitaire. Great for a quick mental boost!

Sulit77’s legit! They got some decent promos and the site is easy to navigate. Just be smart about your bets, ya know? Try Sulit77 now: sulit77

Great insights on strategy and odds-makes you appreciate how AI tools like the AI Tiktok Assistant can streamline decision-making and boost efficiency in unpredictable environments.

Jiliparkvip sounds exclusive! Maybe I can become a VIP player someday. Gotta start somewhere, right? Go VIP with jiliparkvip!

9977bet, not bad, not great. Just another one in the mix. But hey, you might get lucky. Give it a look: 9977bet.