8 steps to get you on the path to greatness — for founders

The idea of doing great work is appealing to almost anyone with a little ambition. It can also seem borderline impossible.

The good news? Paul Graham, the founder of Y Combinator and one of the best thinkers in the startup and tech space today, wrote a how-to guide that lays out exactly how to do great work.

The bad news? It’s 12,000 words long.

So I’ve broken it down into 8 simple, actionable steps you can take to start doing great work, today. And be warned — Graham’s ambition is infectious. So even if you don’t currently see yourself doing great work, this just might make you change your mind…

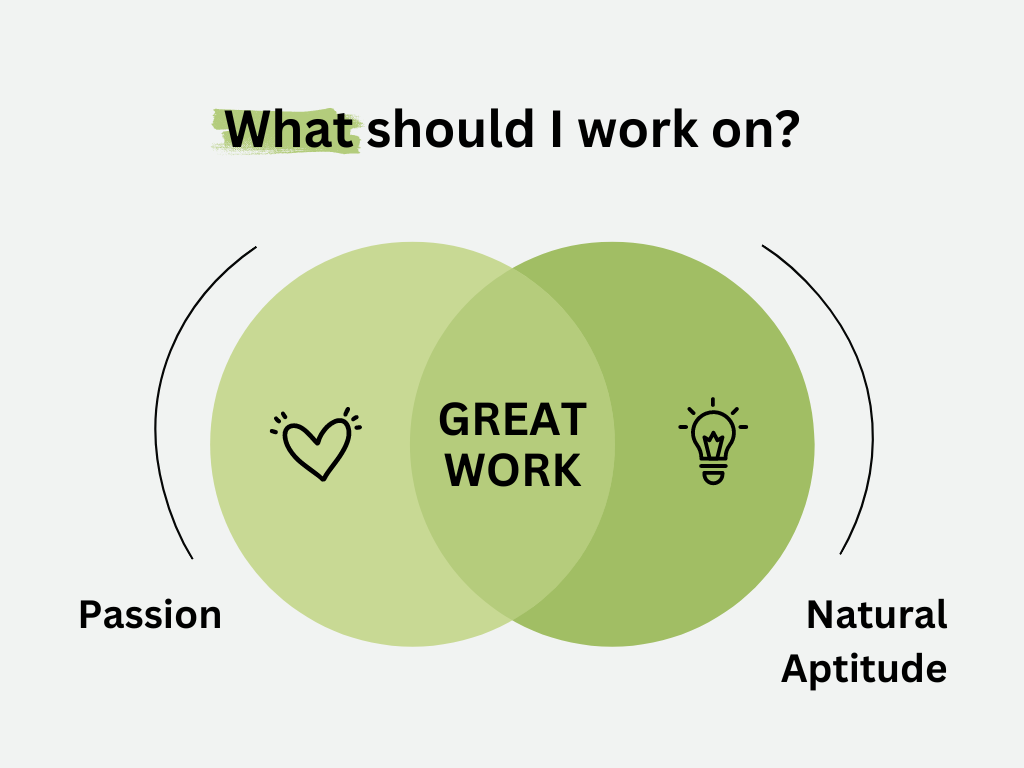

1. What should I work on?

This question might seem overwhelming, and you won’t always get it right the first time. But there are ways to break down the process to make a better, more informed decision.

It’s tempting to look at where the most opportunity — or the most hype — is concentrated, and work backward from there. Right now, AI may seem like the only frontier worth considering, but with over 70,000 AI companies worldwide and a quarter of those based in the US, competition is fierce and success is far from guaranteed.

Passion is the far better starting point. If you are not passionate about artificial intelligence, it will be hard to break into the space and do great work. Natural aptitude is also vital — and the way to find your aptitude, according to Graham, is by working. “If you’re not sure what to work on, guess. But pick something and get going.”

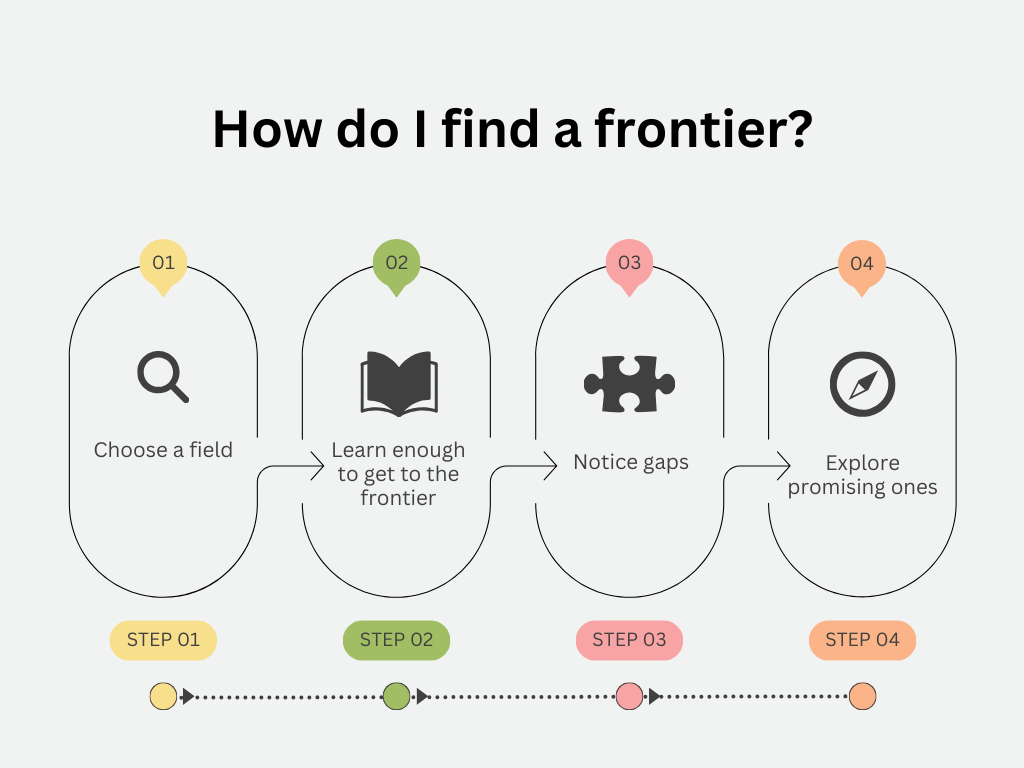

2. How do I find a frontier?

Once you know the area you want to work in, the next step is to learn as much about it as possible. As Graham explains, “Knowledge expands fractally, and from a distance its edges look smooth, but once you learn enough to get close to one, they turn out to be full of gaps.”

Noticing these gaps is its own skill. Take a turn at stand-up comedy and begin asking “Have you ever noticed..?” but about non-trivial things. New ideas come directly from these observations — and if you’re looking to do great work, outlier ideas that others view as unlikely are your best bet.

To achieve this, you have to be comfortable with not having a plan. Graham puts it like this:

“In most cases the recipe for doing great work is simply: work hard on excitingly ambitious projects, and something good will come of it. Instead of making a plan and then executing it, you just try to preserve certain invariants.”

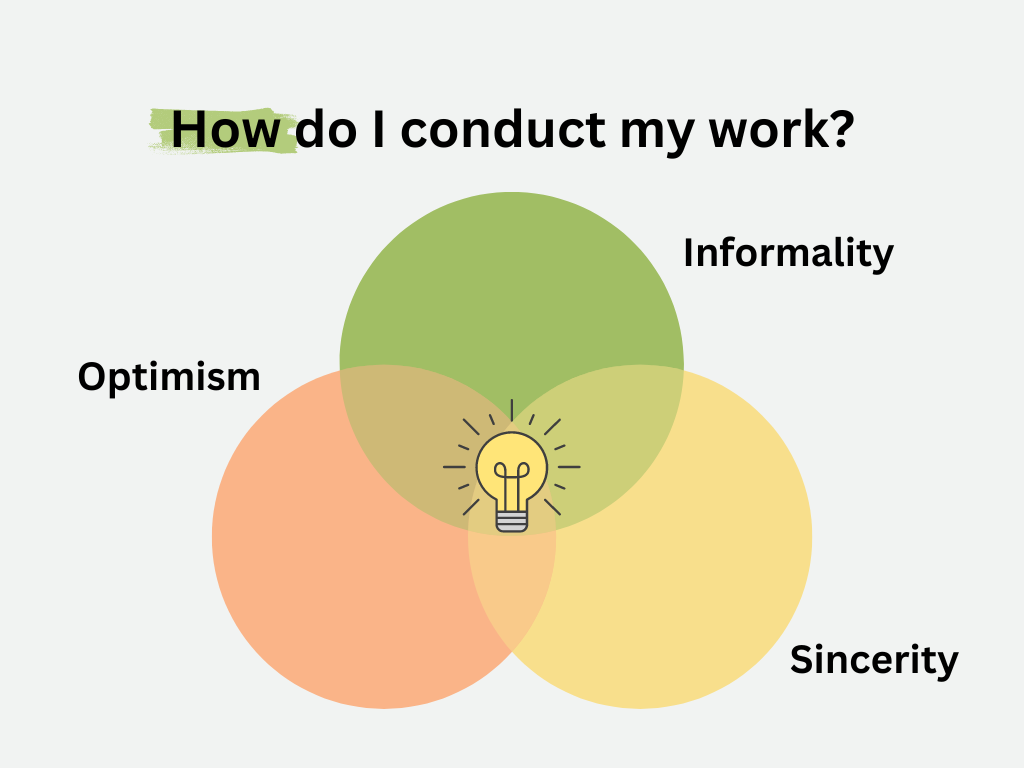

3. How do I conduct my work?

If you don’t know what ‘the best’ looks like in your field, you don’t have anything concrete to aim for. At the same time, don’t try to work in a distinctive style.

That may sound contradictory – but it all comes down to one central idea. “If you don’t try to be the best, you won’t even be good.”

If that’s still sounding pretty vague, Graham has some more concrete advice on how to conduct your work – and yourself.

- Optimism – Pessimism is easy; optimism is harder. It’s easier to criticize than to offer new ideas.

- Informality – An indicator that you have your priorities straight — that you know what’s important. Focus on what you do, rather than how you are perceived.

- Sincerity – Be intentionally earnest and avoid affectation. As Graham says, “you need an exceptionally sharp eye for the truth” to do great work.

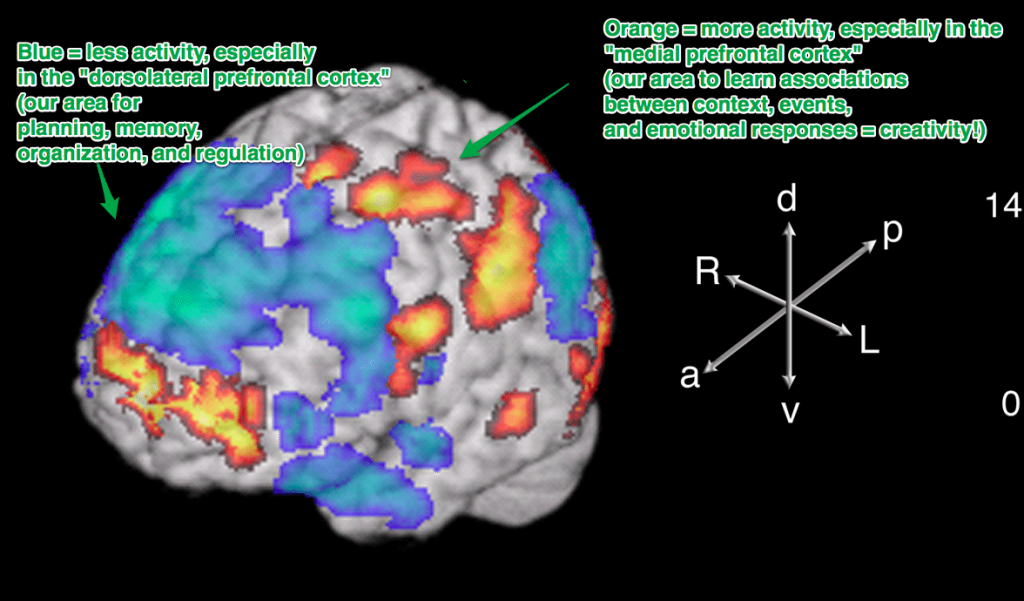

4. How do I cultivate originality?

Obviously, a good idea isn’t enough if someone else got there first. But where do new ideas come from?

Graham says “originality isn’t a process, but a habit of mind.” That’s good news, because it means you can get better at it. But it’s also important to measure your success at original thinking in proportion to your expertise in a certain field. If you don’t know enough about a topic, your ideas might be completely original but inarguably terrible.

“One of the most original thinkers I know decided to focus on dating after he got divorced. He knew roughly as much about dating as the average 15 year old, and the results were spectacularly colorful. But to see originality separated from expertise like that made its nature all the more clear.”

The most important part of cultivating originality is simply to work on something. No original thinker came up with their breakthrough by sitting down and actively trying to come up with a Brand New Idea.

New ideas are a product of their context; the field you’re working in but also your environment. Switch up your surroundings from time to time — work from a different room in your house or go for a walk. Talking to people about your topic of choice and exploring related topics is also a great way to uncover new angles and spot the gaps in your knowledge that could be worth exploring.

5. How do I pick the right idea?

The right idea will probably seem bad to most people. That’s why no one else has explored it before. But if everyone says an idea is bad, how do you work past that mental block?

One method Graham recommends is to think of the ideas as something someone should work on, rather than you. That can help to prevent you from ignoring ‘riskier’ ideas in a misguided attempt to protect yourself. This type of reframing can take time to perfect, but it’s a useful mental trick to get you on the right path.

Other qualities of a good idea:

- It requires rule-breaking. Pointing out a flaw in the predominant world-view is an act of rule-breaking in itself — and it can take a long time for the rest of the world to catch up. Think Galileo, who was sentenced to life imprisonment for believing the Earth orbits the sun.

- It’s ‘religion’-adjacent. Historically, a lot of the biggest scientific discoveries have been hidden in plain sight, and only gone unnoticed for so long because they contradicted the prevailing religious doctrine. Nowadays, this can be anything that people follow implicitly.

- It’s unfashionable. It’s easier to be bold when exploring solutions rather than choosing an initial problem because it’s a longer-term commitment. Reject the impulse to pick a trendy problem and instead explore other avenues, including subjects that are considered ‘complete’ or insignificant.

- It’s self-indulgent. Curiosity will lead you to problems that naturally intrigue you, rather than those that are currently popular. You’re far more likely to discover new ideas this way; you never know what will turn out to be important in the long run.

- It’s a question, not an answer. “A really good question is a partial discovery.” It can be uncomfortable to ask a question that seems unanswerable, that you might have to carry around for a long time. But asking a novel question shows you’re already in interesting territory.

- It confuses you. This one sounds counterintuitive, but you’re allowed to be puzzled by the questions you pose and the answers you come across. As Graham says, “the more puzzled you are, the better … [so long as] no one else understands them either.” And the best ideas raise more questions than they answer.

6. How does a small idea grow into a big one?

The three keys to growing an idea: iteration, risk, and copying.

Iteration is self-explanatory, but it’s worth repeating. Start with the smallest, simplest version — particularly if you are working on a product — and get it in front of people as soon as possible. Your idea will take dozens of forms and you’ll explore hundreds of variations while growing your idea, and this process will shape the big idea it becomes. The final iteration will look different to how you first conceived it, but it will also be bigger and more ambitious than you could have anticipated.

Risk is also key. Graham advises to “take as much risk as you can afford.” That will look different for different people, but it’s essentially betting on yourself. And it’s important to expect, even welcome failure — a failed project can unlock new prospects and ideas as easily as a successful one.

Copying is more of a skill than iteration or risk, which means you need to develop it in the right way. Bad copying is mindless or furtive; good copying is building on or responding to existing ideas. Good copying can also look like taking an idea from one field and applying it to a drastically different one, even in a metaphorical or allegorical sense. Copying, like any other skill, has positive and negative applications.

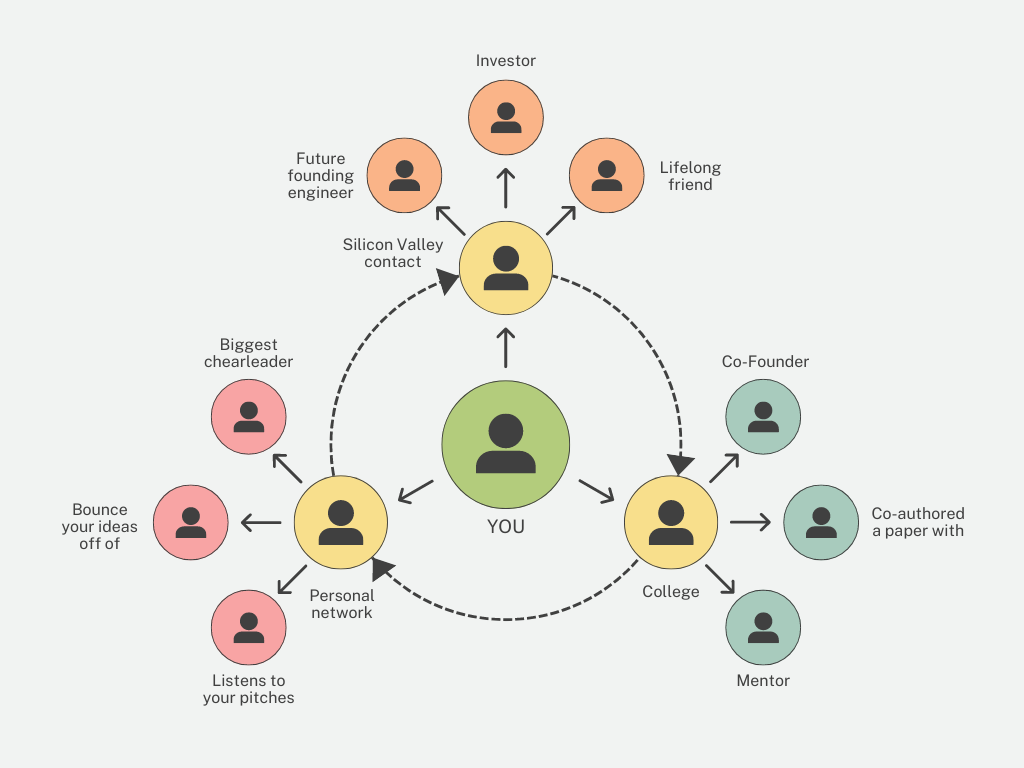

7. Who should I work with?

You might think that the best ideas are the product of one great mind, but that’s rarely the case. Did you know, for example, that the Nobel Prize for Physics has been given to a team rather than an individual every year since 1972? People rarely accomplish something truly incredible completely alone.

But how do you choose who to work with? One way to meet the right kinds of people is to spend some time wherever they congregate — for tech, that’s Silicon Valley, but also MIT and other colleges. Graham warns that it “may take some effort to find the people who are really good, though.” Just because someone belongs to a prestigious institution or a valuable SV ZIP code doesn’t guarantee they’re doing pioneering work.

When choosing colleagues, Graham’s big advice is to “work with people you want to become like, because you will.” Find folks who challenge you, inspire you, and keep you on your toes (intellectually speaking). Surround yourself with people who ask interesting questions. According to Graham, when you find these colleagues, you’ll know it.

8. How do I maintain morale?

Graham calls morale “the basis of everything” — and for good reason. Without it, you will never have the ambition to do great work.

It starts with world-view; having a fundamental optimism is the best way to foster morale. To preserve it, you need resilience. By anticipating setbacks and valuing them as part of the process, you can “innoculate” yourself against this kind of demoralization. Accept that doing great work will require some backtracking at times, but don’t let this deter you.

It’s also easy to let your audience demoralize you, whether that’s your colleagues, consumers, scholars, or the press. Some people will drain your energy without meaning to; others will drag you down with their pessimism. Concentrate on your immediate audience — the people rooting for your success, who appreciate your idea — and avoid letting intermediaries come between you.

The best thing about morale is that the more good work you do, the better your morale will be. Great work is in this way its own motivator, and its own reward. To end on a final Paul Graham quote, “People who do great work are not necessarily happier than everyone else, but they’re happier than they’d be if they didn’t.”

Been finding it hard to locate 188bet? Nhacai188bet.org is a reliable portal. I found that it works pretty well. Check it out and play away! Right here: nhacai188bet

Great breakdown-tyy.AI Tools feels like the go-to compass for navigating the AI landscape, especially with their AI Builder section. It’s smart, curated, and actually saves time.

Jackpotlandapp? Mobile gaming, you say? I’m always lookin’ for a quick score on my phone. Hope it doesn’t drain my battery too fast. Gettin’ the app: jackpotlandapp

I’ve tried several platforms, but Jili really stands out with its smooth interface and great variety of games. The AI features on Jili Online are a game-changer for strategic play. Easy to get started-highly recommend!

8okgame… not gonna lie, I was skeptical at first, but it’s surprisingly good. Give it a shot, you might just be surprised. Check it out: 8okgame