Why the managerial class hates Elon Musk

In the run-up to the 2024 election, we’re doing things a little differently here at Valley Letter. For the six weeks leading up to the election, we’ll be diving into the political scene in Silicon Valley, exploring everything from alternative systems of government to specific policy pitches from the likes of Peter Thiel, Sam Altman, and Ben Horowitz.

In a disillusioning two-party system, expand your mind with these bold ideas that cross party lines and question everything we think we know about politics in America.

This week marks 122 years of the Nobel Prize, with this year’s winners being announced on Monday. Among them is John Hopfield, who won the prize for Physics along with Geoffrey Hinton but is in fact a physicist, chemist, and biologist, as well as the inventor of the Hopfield neural network.

Hopfield is a polymath: a person with exceptional aptitude for and dedication to multiple fields of study. Without his generalist background, he would not have been able to make these contributions – so why does our society actively discourage polymathy?

The History of Polymaths

The term ‘polymath’ has been around since 1603, but polymaths themselves have been around forever.

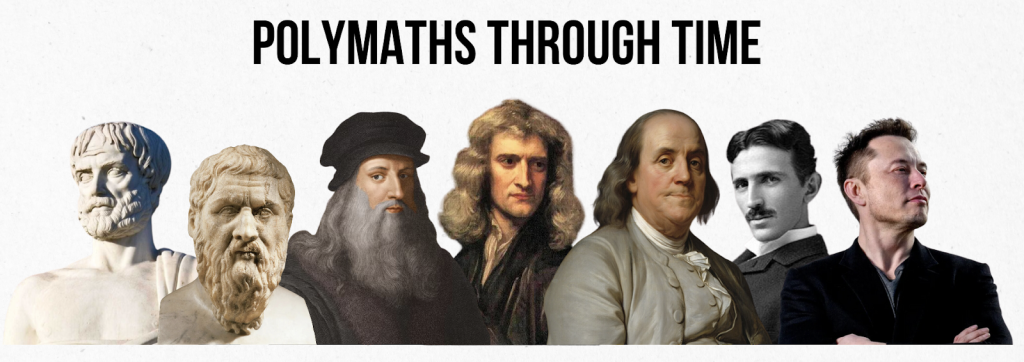

Many of the classic examples come from Ancient Greece: Aristotle wrote on the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, and the arts, while Pythagoras, famous for his contributions to math, was most renowned in his time for his political and theological teachings.

In the 19th century, polymaths got a rebrand with the new name “Renaissance Man”. Inspired by Leonardo da Vinci, who revolutionized both the arts and sciences, the term has been applied to thinkers like Newton, Descartes, and Galileo, as well as more recent figures like Benjamin Franklin and Nikola Tesla.

But the 20th and 21st centuries have seen not only a decline in interest in polymaths, but a near decimation of the group entirely. Modern polymaths typically have to make a modest fortune in one field before branching out to their other interests/aptitudes. A prime example is Elon Musk, whose success at Tesla has enabled his expansion into everything from space exploration to social media.

Why Polmaths Matter

Progress is the product of introducing new ideas to a field. But coming up with new ideas completely from scratch is almost impossible. The solution that humans have been turning to for millennia is polymathy.

More specifically, many of the great discoveries of human history, and even the founding of entirely new fields, come from interdisciplinary study – introducing ideas or methods from one field of research to another.

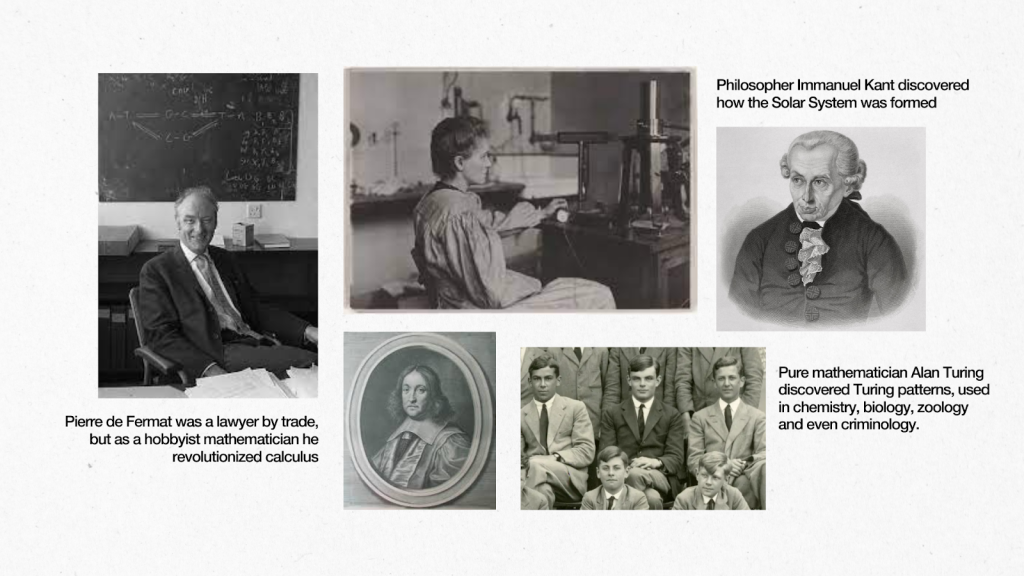

As we discussed in Democracy is the Source of Stagnation, Francis Crick, one of the scientists who discovered the structure of DNA, was actually a physicist, not a biologist. Fellow Nobel laureate Marie Curie won the prize for both Chemistry and Physics – the only person to do so – and combined the two fields throughout her research. Other famous examples include Alan Turing, Pierre de Fermat, and Immanuel Kant.

While discussions of polymathy tend to focus on the sciences, interdisciplinary generalists have contributed significantly to every field, often bridging the arts and sciences. Hedy Lamarr, one of the most beloved actresses of all time, invented a radio guidance system for the Allies during World War II that formed the basis of modern Wi-Fi and Bluetooth. And Dolph Lundgren, of Rocky IV fame, started out as a chemical engineer and even speaks seven languages.

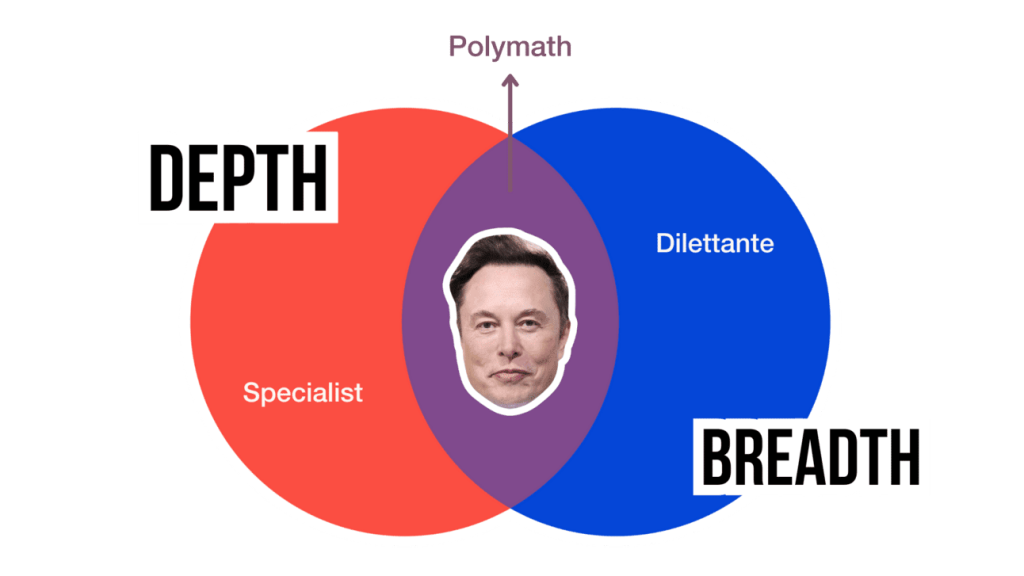

Scientist and humanist Robert Root-Bernstein argues that, aside from polymaths, there are two other types of intellectual: the specialist and the dilettante. While specialists demonstrate exceptional depth of knowledge in a single topic, dilettantes exhibit a superficial breadth across multiple topics, “without regard [for] the broader applications or implications”. Polymathy is the happy medium between the two, demonstrating both depth and breadth of knowledge.

The Death of the Polymath

In academia, a phenomenon has arisen that theorist Waqas Ahmed calls “The Cult of Specialization.” Beginning with the production lines of the Industrial Revolution, specialization in a single skill became associated with productivity and efficiency, taking over as the trait most valued in the workplace. This then spread to education, where pursuing a single line of research within a single discipline became the norm.

But why has specialization remained dominant over polymathy for so long?

PayPal founder Peter Thiel’s theory is that polymaths are becoming scarce because they are “the people who could connect the dots”.

What he means is that institutions like universities and workplaces feel threatened by people who are likely to ask a lot of questions and point out flaws, such as waste or sheer incompetence, among their ranks. Specifically, it’s the managerial class that is killing the polymath.

And it’s not just their penchant for big-picture thinking. Polymaths are seen as ungovernable, as they threaten the authority of the traditional hierarchy and are laregly unmotivated by traditional levers like promotions to managerial roles.

Other prejudices against polymaths come from misunderstandings:

- Attitude Misalignment: Polymaths can be seen as non-committal, unfocused, and lacking dedication or interest.

- Specialization Bias: There’s a prevailing belief that deep expertise in a single area is more valuable than a generalist or interdisciplinary perspective.

- Evaluation Challenges: Traditional metrics like years of experience in a specific field favor specialists, making it harder to quantify the contributions of polymaths.

- Risk Aversion: Companies may view the wide interests of polymaths as a lack of commitment, preferring the perceived stability of specialists.

Government: The Ultimate Managers

Part of why the preference for specialists over generalists has remained so prevalent over time is the role of the government. Officials can be seen as an extension of the managerial class, essentially managers with far greater jurisdiction. As managers, our elected representatives possess all the same biases against polymaths, with one glaring exception: their own ranks.

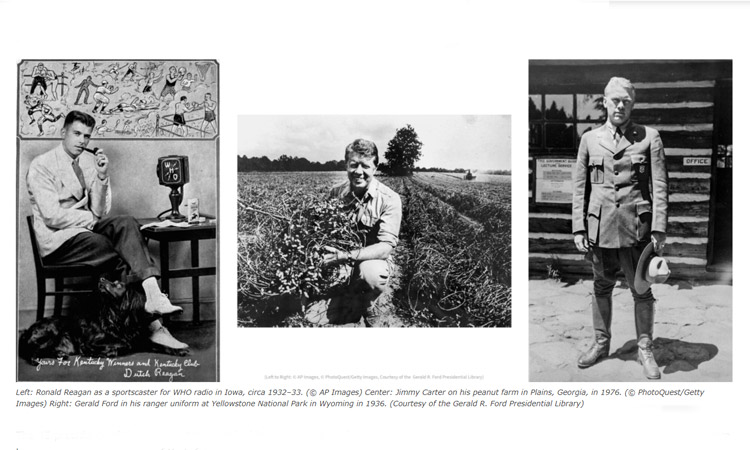

America has a long history of electing polymath presidents. 31 had previously served in the military; 25 had a law background. Lincoln was a postman, Gerald Ford was a park ranger, and Calvin Coolidge was a toy-maker. The US Embassy website even acknowledges that their polymathy “gave them insights into the daily lives of their fellow Americans” through their multiple and varied careers.

It’s no wonder that the presidency attracts polymaths. It’s the ultimate big-picture job that necessitates wearing many different hats and juggling myriad responsibilities. Simply put, it’s a job for a generalist.

But is the presidency the only role that benefits from this kind of individual? Many, including Peter Thiel, would argue not. He describes how “world-class entrepreneurs” are often polymaths, as well as, until recently, most professors.

Very few of us are still working in those linear, assembly line jobs. Contemporary life demands versatility and creative problem solving, not static hyper-specialized thinking.

Polymathy benefits all of us, and striving for it is a sure-fire way to expand your mind and broaden your horizons. So don’t let the managerial class kill your generalist tendencies. Embrace polymathy, and join the great tradition of human curiosity.

Having trouble logging into y888game? I had the same issue, but resetting my password worked like a charm. The site itself is cool once you’re in. Good luck! y888gamelogin

Really enjoying learning about responsible gaming & finding platforms that prioritize security! Seems like PH 799 takes that seriously – easy registration is a plus. Check out ph 799 download for a streamlined experience & secure play! Lots of game options too.

Barganhar plataforma, huh? Sounds Portuguese! Let’s see if I can snag a good deal here. Time to test my luck! barganhar plataforma

Tried out tihay88 recently, and I was pleasantly surprised. Worth a look if you’re looking for something new: tihay88