Einstein, Elon, and why we look for absolutes in everything.

In the run-up to the 2024 election, we’re doing things a little differently here at Valley Letter. For the next six weeks, we’ll be diving into the political scene in Silicon Valley, exploring everything from alternative systems of government to specific policy pitches from the likes of Peter Thiel, Sam Altman and Ben Horowitz.

In a disillusioning two-party system, expand your mind with these bold ideas that cross party lines and question everything we think we know about politics in America.

“Christianity has become toothless.” Or at least, that’s what Elon Musk thinks.

In fact, religions the world over are in freefall, with almost 90% of countries becoming less religious over the last 2 decades. The West, in particular, has become increasingly more secular, with religion largely taking a backseat in people’s lives.

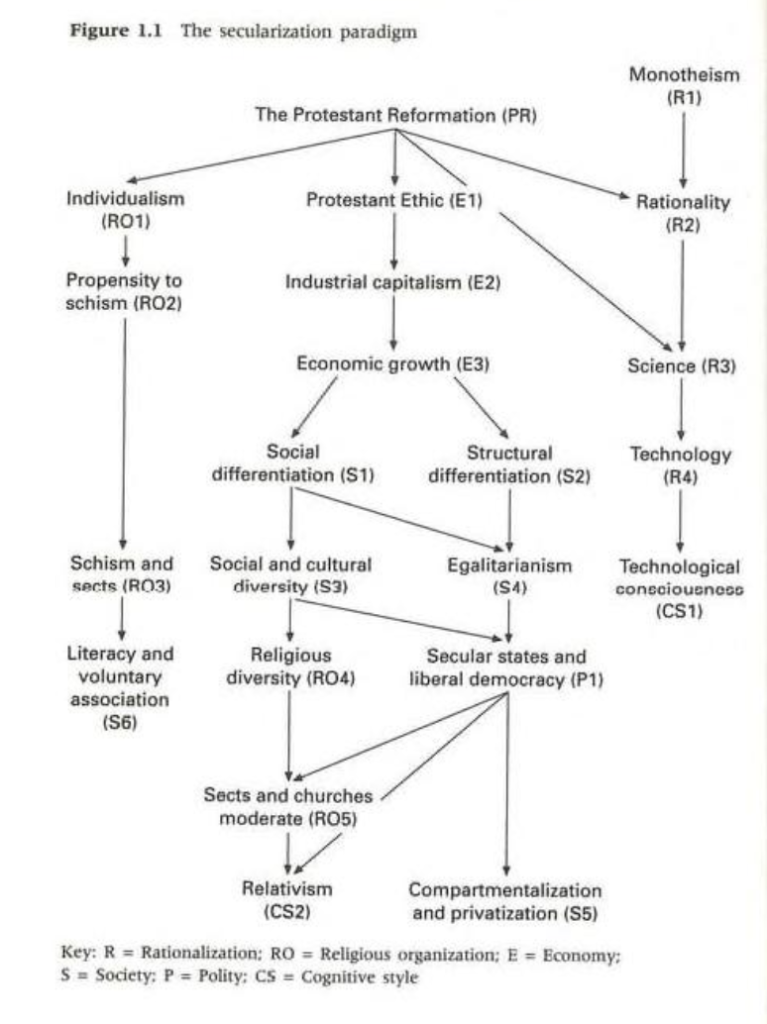

The reasons for this are – to put it mildly – complicated. Here’s one of the most simplified explanations I’ve seen, and even it’s a headache:

This secularization is particularly prominent in Silicon Valley: while only 7% of the US population is atheist or agnostic, that becomes a whopping 50% when you filter for tech workers. Others have written about why this might be problematic: “Silicon Valley is a young atheist’s world — and that’s becoming a problem” from Vox, for example, or USA Today’s “Silicon Valley makes a god of Big Tech. But religious faith is exactly what it needs”. But the purpose of this piece is to explore what’s increasingly replacing religion in the US – democracy.

Seeing the Similarities

At first glance, democracy and religion can seem entirely disconnected. Aside from the fundamentals – they’re both ancient concepts that establish a specific social order – it may seem that they have very little in common.

However, with an open mind, you can soon see certain patterns emerge in how the two operate and the surprisingly similar roles they play in society today.

Rise & Spread

First, the obvious bit. Throughout history, religion was created as a mechanism for social cohesion and control. It gave the world its first governing bodies (via the divine right of kings) and laws. Democracy was created as a direct opponent to this system – and, particularly in the West, it’s been overwhelmingly victorious.

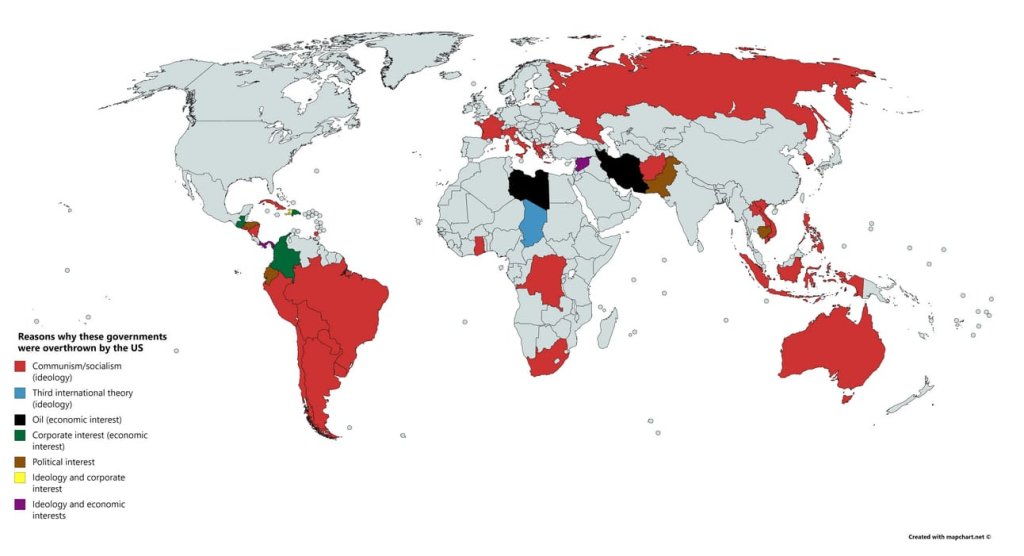

In the last century, democracy has even begun spreading like a religion. From the Crusades to modern Israel-Palestine, war has been used as a vehicle to spread religious ideas and expand or reclaim sacred territories. By backing or even orchestrating regime changes everywhere from Hawaii to Afghanistan, the US has ousted monarchs, dictators and other leaders, often with the intent of installing a democratic system in their place.

Structure

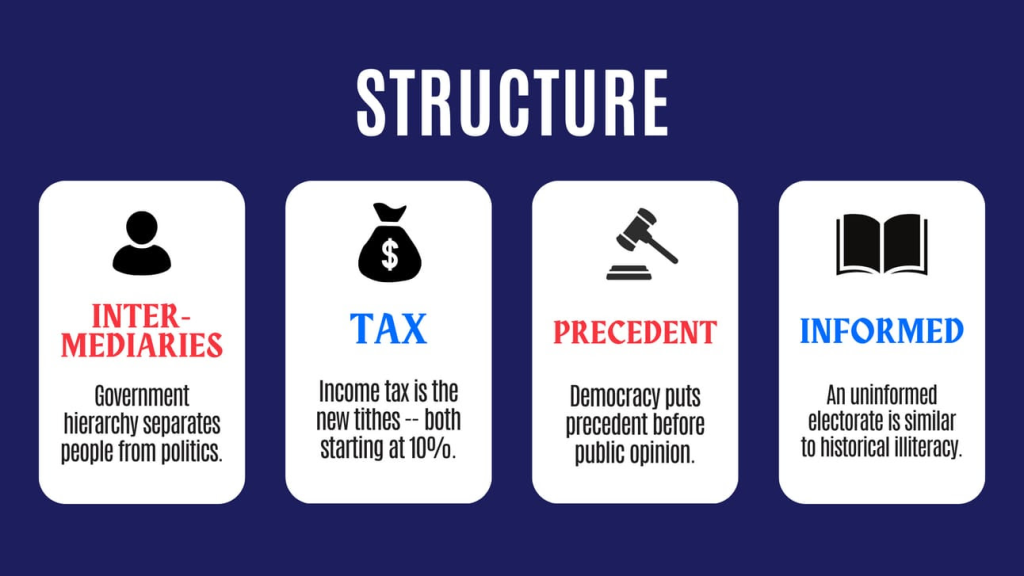

Taking a top-down view of religion and democracy, you can see that both are hierarchical systems with a venerated figurehead and a series of intermediaries separating the figurehead from the general public. But the devil’s in the detail (pun intended):

- Intermediaries: While religions have clergy, democracies have government officials. In the US in particular, this is a complex web of both elected and non-elected officials standing between the president and the average citizen. And with the Electoral College, voters are even more divorced from democracy.

- Taxation: Before we had taxes, we had tithes: 10% of the income or produce of a household that was given to the Church. (Oddly enough, the lowest tax bracket in the US also starts at 10% of income.)

- Procedural formalities: When foreign governments like the CCP criticize Western democracy, one of their go-to complaints is the focus on precedent over genuinely reflecting the interests of the people. In this way, documents like the Constitution and legal precedent are worshiped as quasi-religious texts.

- Low-information participants: While historically religions made use of the general illiteracy of the populace, democracies are similarly run on an uninformed electorate. Creating boundaries to access in both cases has limited dissent and encouraged social cohesion.

Social Function

Democracy is now as embedded in our lives as religion used to be, and as such it’s developed a set of unofficial rules and norms that govern how we engage with it. The most dangerous is that it’s infallible.

Ask yourself this: why does it feel blasphemous to criticize democracy? Why does a critique of this system automatically lump you in with communism, anarchism or the alt-right?

Religions maintain their power and influence precisely because they are above reproach. Historically, challenging the Church has not ended well – just ask Galileo. We’ve now built a new system, but we’ve managed to bake the same flaws into it, through which it garners some of its power.

There are other similarities in social function. Both encourage loyalty, in the forms of devoutness and patriotism respectively. (Note how the US considers displays of nationalism in countries like China as dystopian, compared to our own righteous patriotism.)

Both religion and democracy also promote impatience towards new ideas; studies show that, regardless of the debates, speeches, and media coverage in the run-up to an election, “the majority of the American public is going to vote the way they’re going to vote no matter what.” We are completely unwilling to be swayed from our pre-existing biases.

Did we do this on purpose?

It should be clear by now that democracy and religion are strikingly similar, both in form and function. But the question remains: why?

When a person is raised in a country with a long history of monotheism, it forms a foundational filter through which they interpret the world. Einstein was agnostic, but when asked why he didn’t support the then-emergent theory of quantum mechanics, he replied:

“It seems hard to sneak a look at God’s cards. But that he plays dice and uses ‘telepathic’ methods (as the present quantum theory requires of him) is something that I cannot believe for a single moment.”

Albert Einstein

Psychologists have long argued that faith is a fundamental part of human behavior, whether that faith is in a religion or a system or something else entirely.

Does it matter?

It might not be a problem that democracy is becoming like a religion to the West. But it is important that we recognize this if we really want to understand our relationship with our political system.

But if you are unhappy with a system designed to suppress new ideas, present only the illusion of choice, and place itself above rebuke, what are the alternatives?

As we talked about in our first election special, some in Silicon Valley including Peter Thiel support a Monarch-CEO system, in which executive power is restored and bestowed upon a single “founder-type” leader. Another idea popular in the Valley is technocracy or noocracy, where individuals are chosen for office based on their expertise, particularly in the sciences.

Regardless of your preferred solution, we should feel like we can criticize democracy, point out its flaws and aim for something better. We should be open to changing our minds. And, most importantly, we should remember that democracy, like religion, is a tool that we made to help us navigate the world – it is not infallible, and it is far from divine.

Addendum: Democracy is (Still) the Source of Stagnation

In last week’s issue, we dove into Peter Thiel and Curtis Weinstein’s ideas around democracy and stagnation; this week, we’re bringing some more receipts, courtesy of Pessimists Archive.

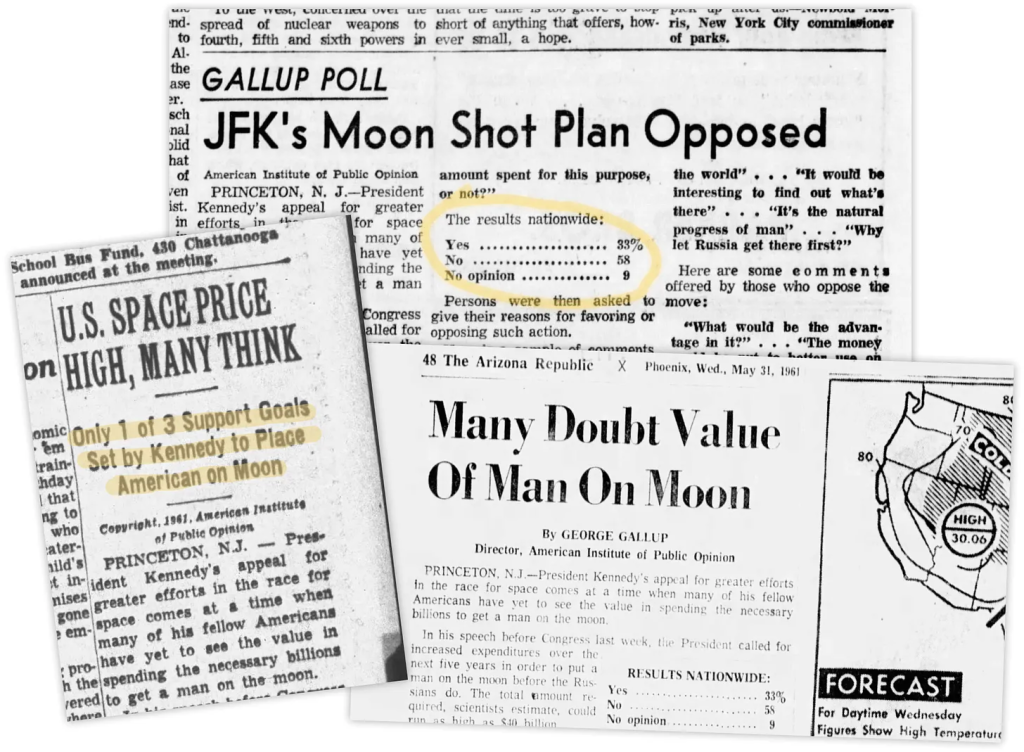

Their archival newspaper records show how some of the US’ most celebrated and pioneering accomplishments were widely unpopular with the general public. Last week, we talked about the Moon Landing, and how listening to public opinion would have prevented a major milestone and the innumerable advancements it’s since produced.

But the Moon Landing is far from the only technological innovation that the public distrusted – and sometimes, the government listens.

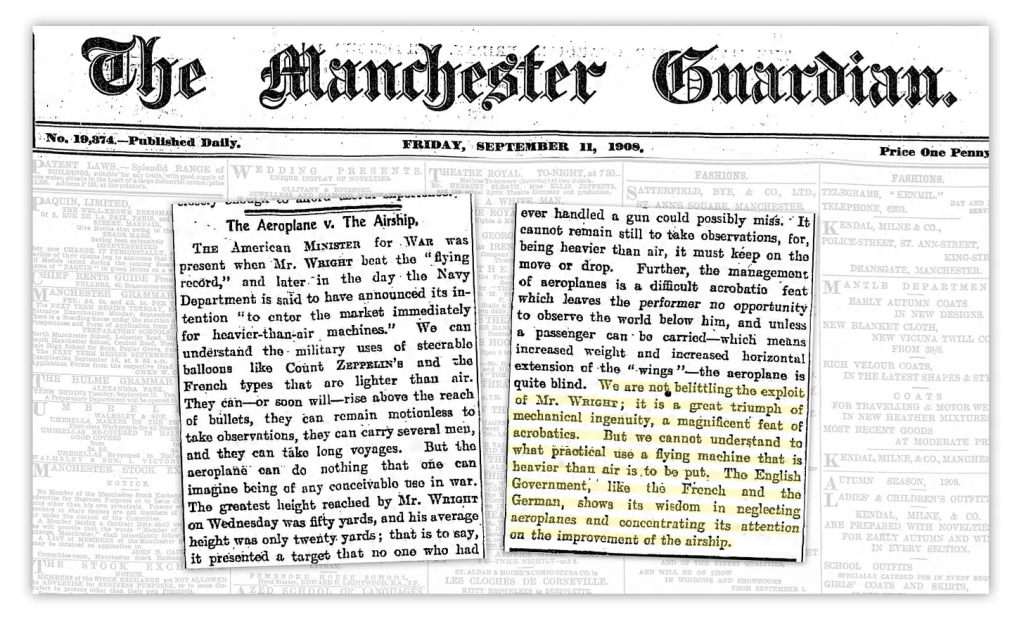

Take airplanes, for example. This article praises European governments, saying Britain in particular “shows its wisdom by neglecting” the nascent technology, which it describes as having no “practical use.”

It is a trend throughout human history for the public to be disinterested or short-sighted about new inventions and technologies. That’s why the burden must fall to governments to be more long-sighted – to take bold new directions and, when necessary, “sell” the general public on science and technology.

One of our greatest achievements was opposed by the majority of US citizens. If we want to continue to make history, we need a leader with bold ideas and unwavering ambition. Who that leader will be remains to be seen.

Alright, ktobet, let’s go! Heard good things about the odds here. Gonna give it a whirl and see if I can win some beer money. ktobet