Playing to play vs playing to win: How to make sure you’re following the real rules, and not the ones we set for ourselves

We all get in our own way.

In sport, it’s often the simple tactics that triumph over showy plays. It’s all about following the real rules of the game – and not making up new ones.

This is how to stop getting in your own way — and start playing to win.

Playing to Play (PTP)

PTPs value impressive execution over success.

We see this in football, when an overly-complicated trick play goes wrong. They’re impressive when they work, but often a standard Hail Mary is more likely to see results. Pride gets in the way.

The same happens in startups.

Some paths to success are seen as better than others. One example: there’s a lot of (deserved) pride in being fully bootstrapped. But that mindset – and that pride – can interfere in the long term.

Many startups fail because they’re playing under a self-imposed handicap.

PCA Predict is one of those startups. They bootstrapped to $25M and were offered $100M for the company in 2015. They rejected it, but ended up selling for ~£83M in 2023.

We admire their ambition, but they lost sight of the real goal.

Example: Viddy

Video-sharing startup Viddy was a sensation last year. Twitter offered to buy the company for £100M – but CEO Brett O’Brien refused.

He thought they were the next Instagram, who’d just been bought for $1B. He raised more funds from VCs but it wasn’t enough. Facebook curbed distribution and monthly users plummeted.

Viddy went from 30M monthly users to just 5M – an 80% drop in 1 year. And O’Brien was removed as CEO.

He was playing under a needless handicap – he was playing to play, not playing to win.

Playing to Win (PTW)

Viddy’s competitor, SocialCam, is one example of an anti-PTP. It raised less capital and received a lower valuation, but sold for $60M months after launch. They weren’t the next Instagram but they knew how to play the game.

A PTW understands the rules of the actual game.

Many say the NBA has gotten boring because it’s now ‘just about taking shots.’ Plays are simple + rely on repetitive 3-pointers and rebounds. There are a few reasons for this but the reason it’s stuck is simple:

It’s a more straightforward vision of the game. So it’s more straightforward to win.

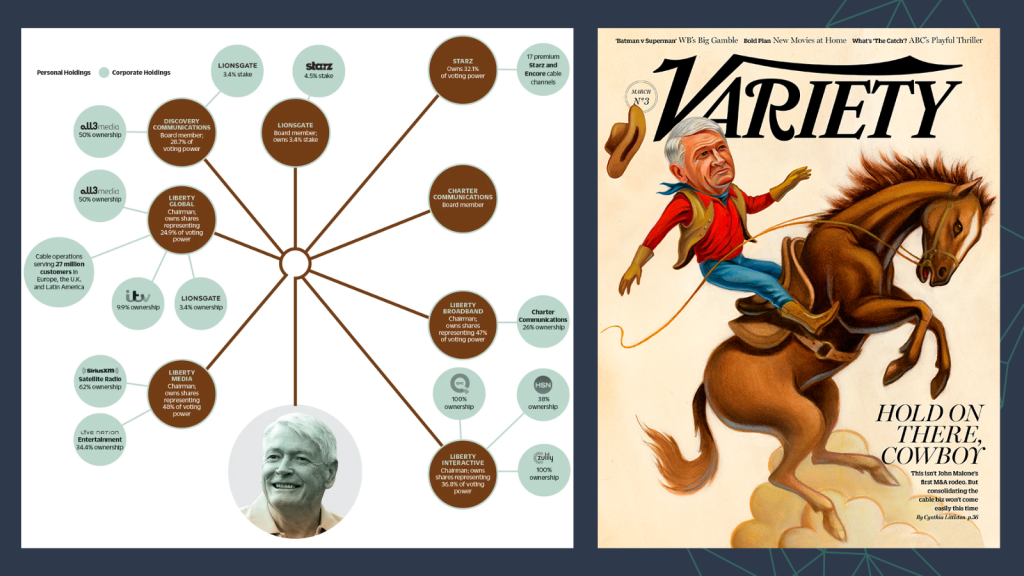

Example: John Malone

As CEO, John Malone made Tele-Communications Inc. the biggest cable company in the US. He knew how to work the industry and regs to his advantage.

He didn’t try to be a ‘pioneer’, he just wanted to make the most $.

He never chose to make things harder for himself.

Maestros – The Exception

Maestros are PTPs that win. It happens, but it’s rare.

Maestros break the rules, add self-imposed handicaps, and still succeed. The problem is, you can’t bet on becoming one.

Roger Federer is definitely a maestro. He uses the notoriously more difficult one-handed backhand over simpler alternatives. But he’s also dominated the sport for decades.

He’s making things more difficult for himself, and winning anyway.

Example: Martine Rothblatt

Rothblatt founded biotech company United Therapeutics to save her daughter’s life. She manufactured a drug that its founders at Glaxo Wellcome thought would never be profitable. But from the $1B+ she’s paid to Glaxo in royalties, she seems to be doing well.

Rothblatt’s also put money into developing electric helicopters to combat their carbon footprint. She’s the perfect example of someone playing by a more difficult set of rules.

But she’s managed to balance a strong revenue with her personal philosophy.

She made things more difficult for herself and still won.

Playing A Different Game

Not everyone’s playing the same game. Founders can have different priorities; they can want to make $ and still be ‘pioneers.’

Clean energy startup Clean Planet has a valuation of $1B – and a clear ethical objective.

Cultural climate can change the rules of the game, too.

Eg: Valley startup culture is the opposite of Japanese corporate culture. Even as Japan becomes less risk-averse, the path to success can still look very different. Sales cycles are long and the VC landscape is dominated by banks.

So startups have to adapt to this rulebook.

It’s like Seve Ballesteros at the US Opens – he undoubtedly knew the game, but only the European rulebook.

The Lesson

Warren Buffett said, “I don’t look to jump over seven-foot bars; I look around for one-foot bars that I can step over.”

Don’t make the game more difficult than it needs to be.

Understand the real game, and you’re headed in the right direction.

Downloading the CasinoPlusAPK right now! Fingers crossed for some beginner’s luck! Let’s see if it’s as good as everyone says. Get yours here: casinoplusapk